Main Menu

Through The Lens of William Thompson

National Geographic Photojournalist & Loving Father

While serving as a photojournalist for the National Geographic in the mid-1980s, I was presented with a Rolex Explorer as part of a joint promotion by the magazine and the Swiss watch company – I opened the box, immediately put it on, and started a journey together that would last 36 years.

I had long wanted a Rolex, as my father wore one all the time, which was to become mine, but it somehow disappeared at the time of his passing. Now, I was given this beautiful instrument to commemorate an incredible time in my life. I continued working for the National Geographic for a number of years, and 36 years later, I continued wearing the Rolex. It never left my wrist, other than for an occasional cleaning – that is, until March 2021.

I do not want to pass away and have my loyal Rolex disappear, as did my father’s watch. Thus, I had the great honor of giving my inscribed Rolex Explorer to my son Parker on his 30th birthday. My wrist feels light, but I love the idea that my Rolex has the opportunity for another 36 years of appreciated existence. What a lovely and meaningful gift for a son to receive from his father, wrapped in memories.

That watch has certainly seen a substantial part of the earth. If it could talk, here is one of the stories it would tell…

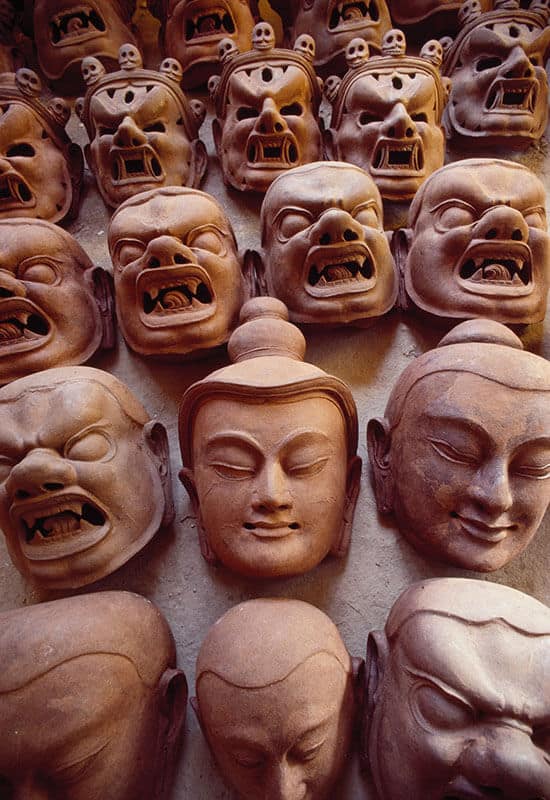

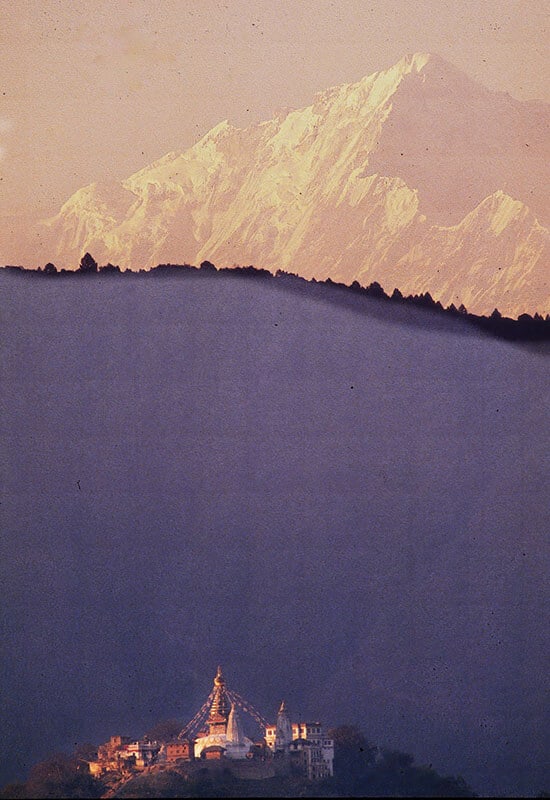

The Boudha Stupa in Katmandu is one of the largest stupas in the world with an energy unto itself.

Kathmandu Valley

Three years living in Nepal with Kathmandu as my home base, I produced three life-changing stories for the National Geographic. They included the Kathmandu Valley, which had not been open to the outside world for very long; Mount Everest from the Air, filming the first (and only) full-aerial view of the top of the world; and the Heart of the Himalaya, a shared assignment with Galen Rowell shooting in the north side, and me in the south (featured in next month’s sequel).

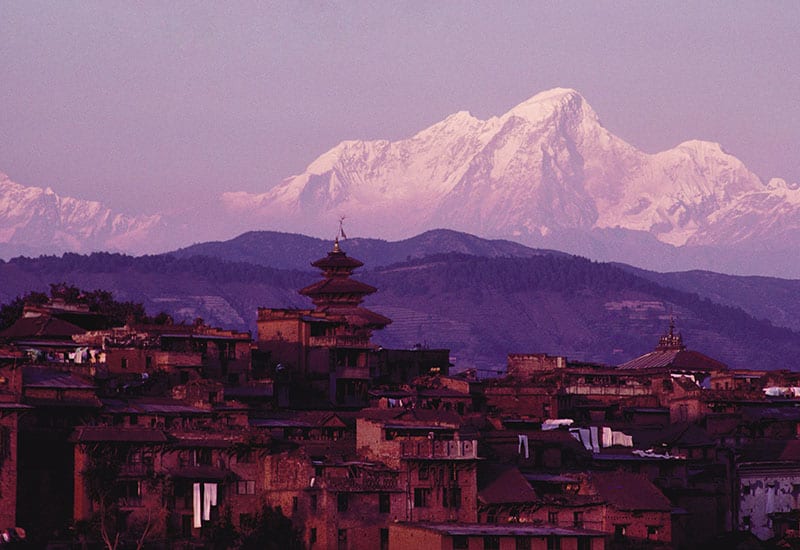

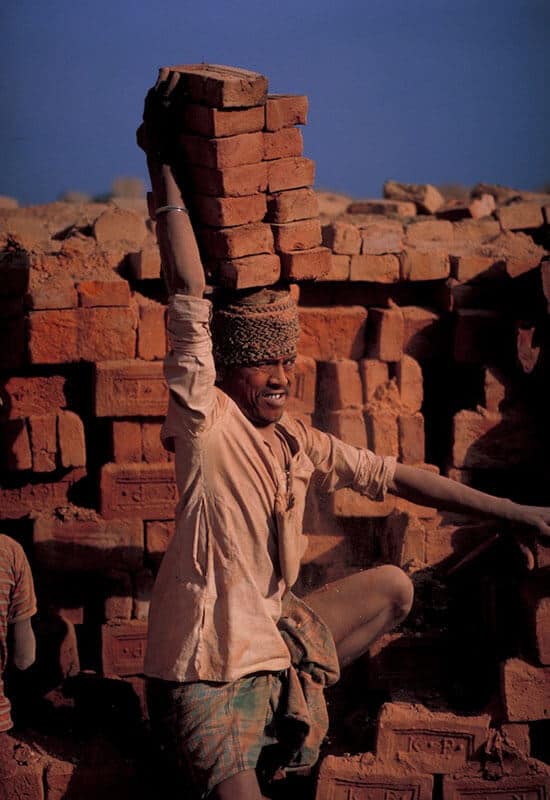

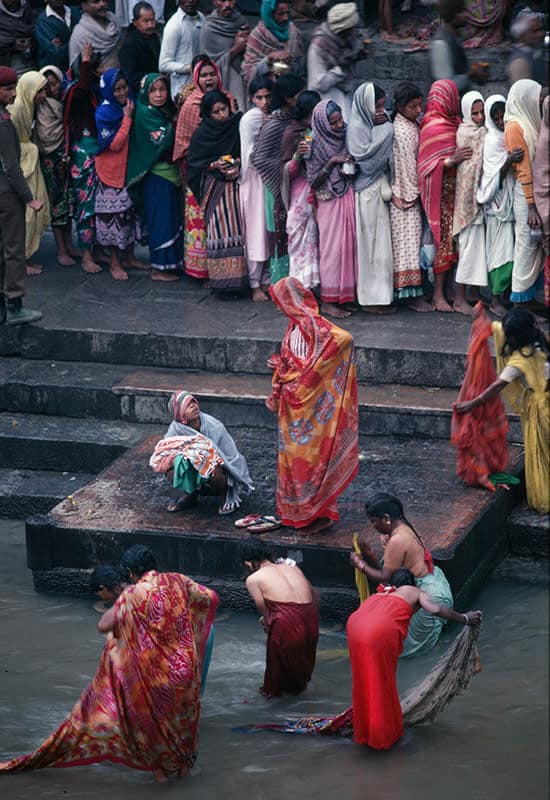

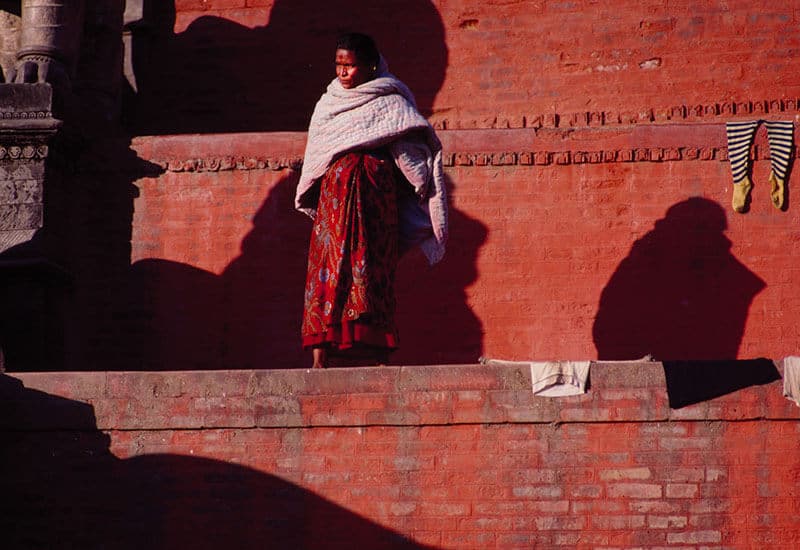

Kathmandu Valley was a gold mine for a photographer and film maker at that time. I could not wait until the first morning rays of sunlight sliced across the walls of the high mountains. I was up early each day, loaded with canisters of film, camera in hand, anxious to dive into the sea of vital color and textures of the daily life of the Nepalese people.

Viewing the thousands of images takes me back to the sounds, the colors, the smells – the vitality – of this astonishing place in the early 1980s.

Kathmandu Valley is a gold mine for a photographer, with its generous display of colors and textures.

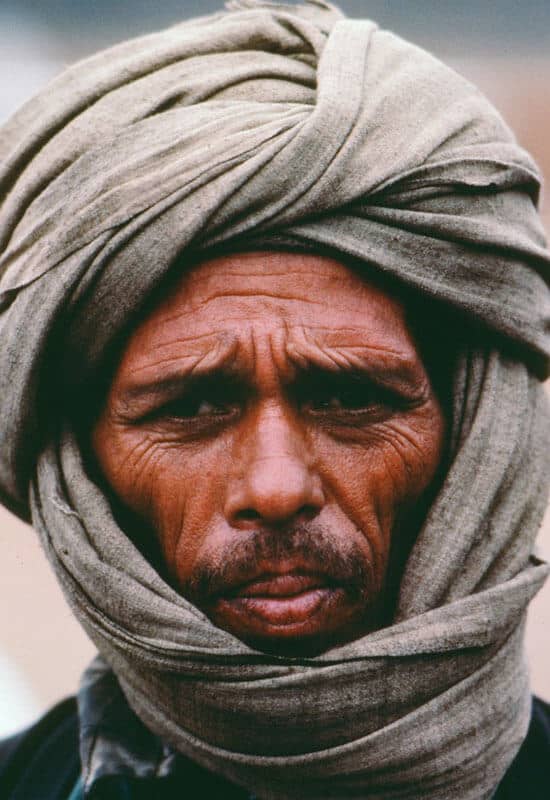

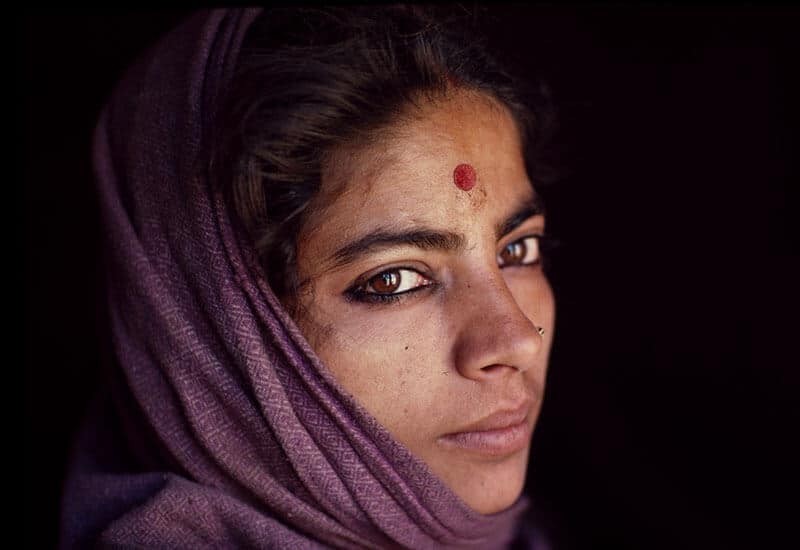

There was never a moment of boredom as I filmed a world that had remained unchanged for centuries, but that was coming to an end. Kathmandu had been and still was at that time in history a place of power, a functional kingdom. It had been the crossroads of trade between a powerful Tibet and its southern trading partner, India. As a trained anthropologist, I knew the way of life the Nepalese had known would soon disappear, now that the political environment was changing, now that it that it had opened up to the outside world.

For a year, I was given the opportunity to tell the story, visually, of this changing moment in time. The daily life of Kathmandu was a marvelous caldron of life, color, textures, and a multiplicity of cultures. One moment I would be sitting beside a Tibetan boy dressed in yak skin robes, and a beautifully dressed Newari woman, her ears ladened with gold, would stroll past. The atmosphere was intensely dense, beautiful, and exciting. As a journalist and as an artist, I was completely free of any direction or commitments, other than the comment by the brilliant National Geographic editor, Wilbur Garrett, “f8 and be there.” In other words, my job was to “get the damned pictures.”

Kathmandu had remained unchanged for centuries, a functional kingdom at the crossroads of trade between a powerful Tibet and its southern trading partner, India.

Mt. Everest from Air

The next assignment was very different, and truly an unplanned uber adventure: filming Mount Everest from the Air. The director of photography at the NGS sent me a telex: “I have a short assignment for you…”

For 10 years, renowned adventurer and mountain photographer Bradford Washburn had been working diligently, almost manically, to create an opportunity to overfly and photograph Everest. These flights where to be his highest personal achievement. Brad had always been a star—as a mountaineer, as the director of the Boston Museum of Science, and as a bigger than life inventive being. Through the 10 years, Brad had brought together the Museum of Science and the National Geographic (the deep pockets to accomplish his Everest project). Brad was living the dream and he planned not only on photographing Everest, but also creating the first and only, and still the gold standard today, map of Everest.

As the first person on earth to film Mount Everest from the air, it did not disappoint.

Brad had procured a specially outfitted Lear jet to do the oblique image making with his famous WWII aerial camera. The jet was also radically modified to hold the huge photogrammetry camera for the mapping project. The plane and crew, along with an engineer and spare parts, were waiting in Sweden to be given the go ahead to travel around the world to meet Brad in Kathmandu. In addition, a Pilatus Porter Swiss acrobatically rated turbine aircraft was retained in Kathmandu, with special modifications to the aircraft to allow the sliding door to be opened at altitude.

Circling around the face of Everest offered a rare opportunity to photograph all sides of the mountain.

My job was to simply tell the story of Brad filming Mount Everest—a sidebar. Not much pressure, catch the prep for all of his efforts , and perhaps go on a flight or two, filming Brad filming. Should be relaxing, great fun.

I quickly became close friends with our interlocutor, Dhurba Mathema, a lovely, older Nepali who could cruise through the thick and dark ranks of the Nepali power structure. A good man and so very tactful. Dhruba, for weeks, had been greasing the skids in the opaque Nepali political structure. A difficult and stressful job at best.

The project was progressing well. And then things started to unravel. Brad was running into resistance and some partial meltdowns of the commitments by the Nepali governmental agencies who would make the final decision for us to fly. Then, Brad’s wife had become ill. One morning I awoke to the sound of an envelope sliding under my door. It was from Brad, informing me that he was taking Barbara to the hospital in Bangkok and he would be back in a few days. This was not to be. Barbara condition had worsened, and the decision was made for them to return to Boston, via medivac…a decision that saved her life.

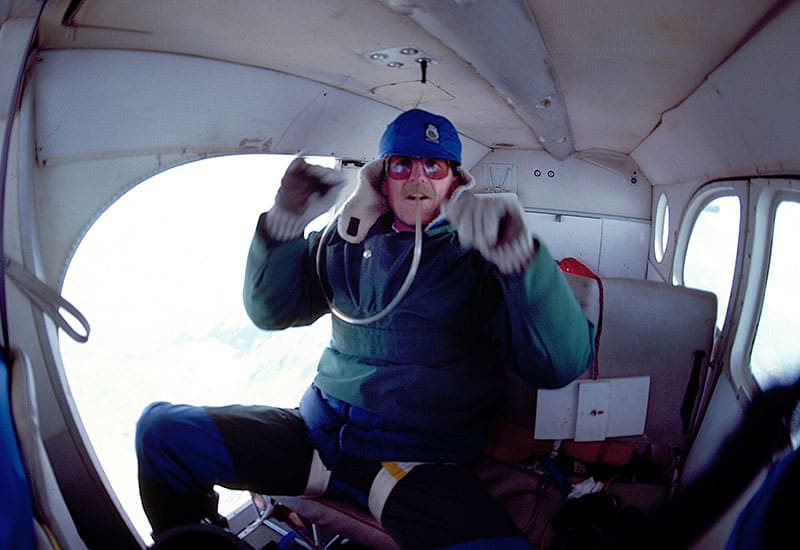

William Thompson (r) recalls that the Pilatus flights were like being “a bug in a thunderstorm,” as the jet stream was slamming into the tops of the peaks.

The Show Must Go On

Garrett had committed using Brad’s Everest imagery in National Geographic’s upcoming 100-year anniversary issue, “Exploring the Earth,” and he had pumped huge amounts of time and money into this project—specially-fitted aircraft, crew, planning, and prep—and the star of the project was not coming back. My role in the project suddenly changed significantly…from filming the primary photographer to becoming the primary photographer.

No longer just a journalist along for a ride, my stress level also changed. After several no-gos imposed by the local government for no apparent reason, sometimes while we were waiting at the aircraft, one morning we received the thumbs up. With Brad out of the loop, my good friend Barry Bishop, who climbed Everest in 1963, was brought on board the project to help document the story. We were ready to go!

The Pilatus flights are best described simply as a bug in a thunderstorm. The jet stream had dropped down and was slamming into the tops of the peaks creating dangerous drafts of air. On one occasion, Barry asked to fly close to Ama Dablam. Barry had done the first ascent of this magnificent peak and he wanted to see it from our once-in-a-lifetime viewpoint. Wick, our pilot, told us this was a dangerous thing to do considering the rotors of air pushing us around.

As he was explaining, we were suddenly hit by a powerful downdraft as we came across the face of the peak, the plane went into a dive, and Barry was thrown up against the back of the plane, knocked unconscious. I was sitting on a wooden milk crate, filming, and was bashed against the pilot’s seat. Our military observer went into projectile vomiting. The sliding door was open and some of my camera gear, which I had so thoughtfully arranged on the floor around me, evaporated.

All I could think of as we screamed towards the ground was, “I wonder if it will hurt when we hit the moraine.”

The Everest mission offered a complete aerial view of the top of the world as seen never before – or since.

Our amazingly-skilled pilot, Emile Wick, trained by hours of high mountain flying in the Himalayas, saved us. We didn’t finish the flight that day—we were all enormously twisted by this close call. We just turned tail and headed back to Kathmandu, musing about how our luck had been good. Very good.

We flew the Pilatus on photographic missions on numerous occasions. We flew with that little plane with the door open to 28,000 feet. We circled around the face of Everest. I reflect now that I was not afraid, despite our close call. I was focused on this rare opportunity to photograph all sides of the mountain.

Then the Lear jet arrived. A week followed with nonsensical, albeit temporary, revocations. Expenses were mounting, with us and an aircraft and crew from Sweden, who were sitting on standby, day after day. Something had to happen soon. The Chinese team and the Indian Ambassador met again, and finally gave the go ahead. We could fly.

The end result of this wonderful adventure was thousands of images of the incredibly beautiful Mount Everest.

A Sacrificial Goat?

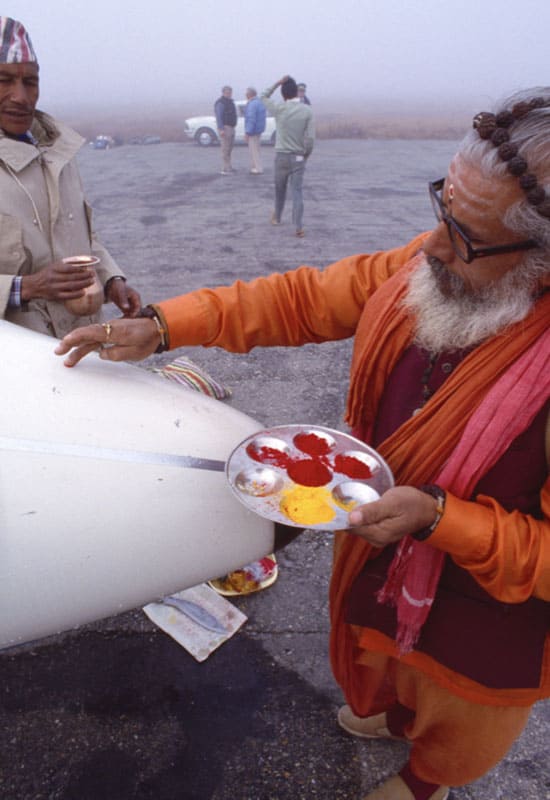

We gathered on the tarmac of Tribuvan Airport, everything checked and the excitement was high… the first person on earth to film Mount Everest. We climbed aboard, the door to the Lear closed, and the pilot called the tower, ready for takeoff. The tower instructed our pilot, Berndt, to taxi to the head of one of the runways and hold. We sat there and sat there, and then the tower instructed us to return to our parking spot. We had not fulfilled all of the Nepali Governmental requirements to fly—the crucial puja or ceremony had not been performed on the aircraft.

Crushed, we returned and contacted our wonderful liaison Dhruba to arrange a puja, which was scheduled for the following morning. Once again, we assembled at the airport, loaded our gear, and stood by. A beat-up Toyota taxi arrived on the runway, and the sadu, or holy man, dressed in saffron robes and carrying all kinds of paints and holy waters, stepped out of the compact car. He opened the trunk and retrieved a lovely little goat. The sadu began anointing each of us with his color paints. He anointed the gleaming, pristine Lear jet, smearing color everywhere, including inside the cockpit, as an anxious crew responsible for the aircraft looked on. I knew, and Barry knew, what was about to happen. The crew did not. The cute little goat with a marigold in its mouth was about to be sacrificed.

The crew was required to fulfill all of the Nepali Governmental requirements to fly, including the crucial puja or ceremony on the aircraft – the sacrifice of a goat.

Holy water would be poured carefully along the little goat’s back. If the hair did not rise up, then the sacrifice would be cancelled and the entire event would have to take place on another day. A good result would be if the little goat’s hair responded as it should. The sadu did a few more paintings on the jet, poured holy water on the little goat’s back, then unwrapped a very shiny kukri, or Nepali knife, poured holy water on it, and handed it to his puja assistant, who promptly chopped off the head of the goat, grabbed its body, and ran around the jet spewing the goat’s pumping blood all over the aircraft. The sacrifice was a declared a successful one. We would now be allowed to fly.

The end result of this wonderful adventure was thousands of images of the incredibly beautiful Mount Everest—a complete, aerial view of the top of the world, as seen never before, or since.

If Your Watch Could Talk What Would it Say

Even if you only explore your universe within, life is an incredible adventure. But for those who embody the perpetual quest for doing things only imagined, for those who are simply destined to rise to the top, they prefer a timepiece that will never let them down – while making a statement, too.

If your watch could talk, what would it say? Would it tell tales of great triumphs at the pinnacle of your profession, or talk of the tough lessons that come with living life on your own terms? Would it walk us down the road less traveled, ascend to the world’s highest peak, or share discoveries at the depths of the deepest oceans?

Would it dare to explain the scuff marks, dings, and dents it endured all along the way, offering a tangible tour of your life, like hieroglyphic signs of moments that might otherwise never be remembered?

Perhaps most telling would be the moment you decided to pass on your treasured timepiece to a loved one – just as National Geographic Photojournalist William Thompson did this year. For his son Parker’s 30th birthday, he handed down his Rolex Explorer with the hopes that one day Parker would continue the tradition with his own son.